A SLAPP in the Face to the Abuse of Court Processes

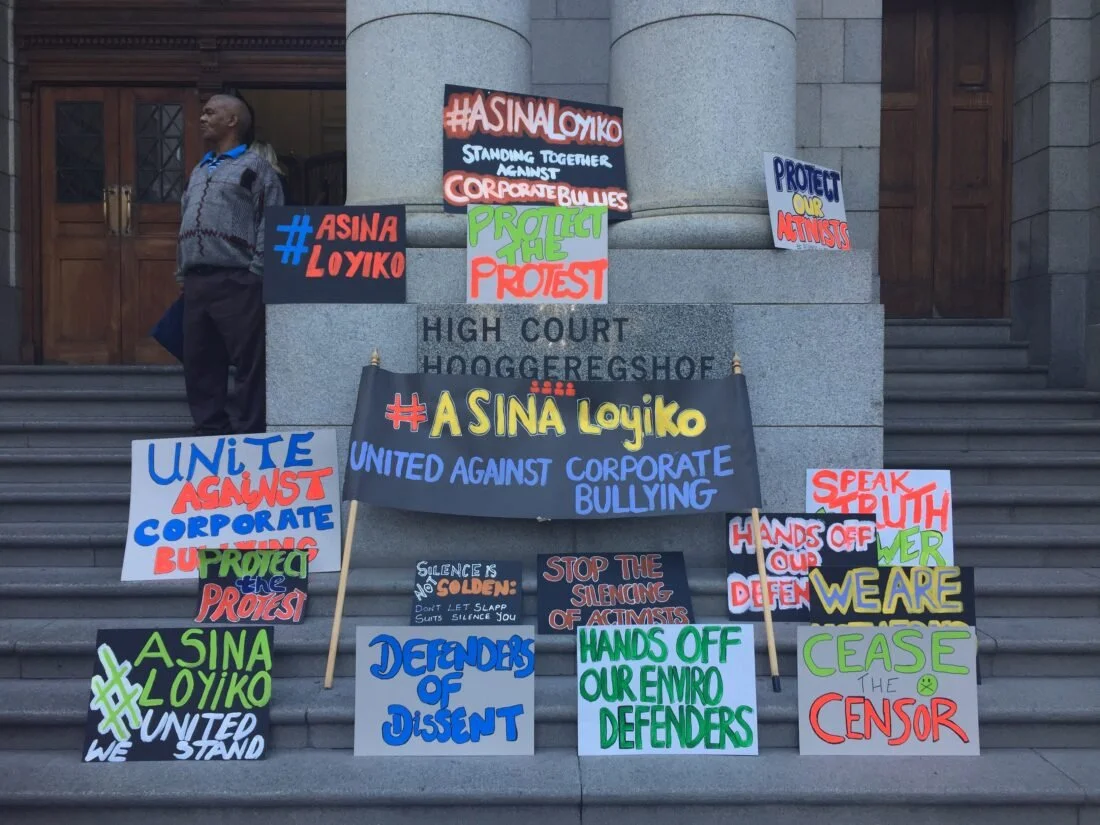

“Protest signs outside the Western Cape High Court in 2019” was published by the Centre for Environmental Rights on 15 November 2022.

Editors’ note: on 7 March 2023, the South African Institute for Advanced Constitutional, Public, Human Rights and International Law (SAIFAC) in partnership with the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung hosted a seminar discussion on the Constitutional Court’s recent judgment in Mineral Sands Resources (Pty) Ltd v Reddell. The seminar examined different perspectives on the judgment and the application of the “SLAPP” defence in South African law. This article was authored by one of the seminar panellists.

A “SLAPP” suit is strategic litigation against public participation and has its origin in the United States of America and Canada.

Introduction

The hallmark of a SLAPP suit is its lack of merit, having been brought to discourage a party from pursuing or vindicating their rights, often with the intention not necessarily to win the case, but simply to waste the resources and time of the other party until they abandon their defence. SLAPP suits are frequently brought as defamation claims, abuse of process, malicious prosecution, or delictual liability cases.

Having only originated in America in the 1980s, this defence is novel in the South African context and was recently considered by the Constitutional Court for the first time in the case of Mineral Sands Resources (Pty) Ltd v Reddell (Mineral Sands).

The dispute in Mineral Sands originates from three defamation suits instituted by Australian mining companies (mining companies) and some of their executives. The defendants in the suits are environmental lawyers and activists (activists).

The mining companies are engaged in extensive mining operations in the exploration and development of major mineral sand projects in South Africa. There is fierce community opposition to these mining activities relating to the alleged duplicitous and unlawful nature of the mining companies’ operations which were said to be ravaging the environment. In the course of this opposition, the defendants were alleged to have made statements that were defamatory to the mining companies. In response to these allegations, the activists raised a SLAPP suit defence in the form of a special plea.

The Court had to determine whether our law accommodates a SLAPP suit defence under the abuse of process doctrine and, if not, whether it ought to be developed.

The mining companies argued that a SLAPP defence could not succeed where the case has merit. The activists on the other hand submitted that the merits of the matter are irrelevant and that the motive behind the launching of the lawsuit is the only element.

Contemplating these arguments, the Constitutional Court had to consider and balance the right to freedom of expression against the right to access to courts. The question is whether the Court struck an appropriate balance between these competing constitutional rights.

In order to answer that question, it will be helpful to briefly consider the role and importance of each right.

The right to freedom of expression

The activists argued that a SLAPP suit violates the right to freedom of expression in that it was brought for the sole purpose of silencing public criticism.

The importance of the right to freedom of expression cannot be overstated. The right to freedom of expression commands an important place in our constitutional landscape. It is a right that lies at the core of our constitutional democracy, “not only because it is an ‘essential and constitutive feature’ of our open democratic society, but also for its transformative potential”.

This was recently emphasised in Qwelane v South African Human Rights Commission, where the Constitutional Court articulated that the right to freedom of expression “is the benchmark for a vibrant and animated constitutional democracy like ours”.

The right to access to courts

The mining companies however argued that to dismiss a meritorious suit, for whatever reason it is brought, would be in violation of the right to access to courts.

The right to access to courts in section 34 of the Constitution is essential for a constitutional democracy under the rule of law. A fundamental principle of the rule of law is that anyone may challenge the legality of law or conduct. The rule of law seeks to promote the peaceful institutional resolution of disputes and to prevent the violence and arbitrariness that results from people taking matters into their own hands.

Did the Court strike the appropriate balance?

The Court held that an abuse of the court process can take various forms and does not have any defining central feature. It is a factual consideration, depending on the facts of the case.

“The question that remains is how this defence will work in practice in light of the fact that this special plea requires a consideration of the merits at a preliminary stage of the trial before any evidence has been led.”

In a case where a plaintiff institutes litigation with little to no prospects of establishing a case, this constitutes “abusive litigation”. It would not be easy to establish a case of abusive litigation, but if one can do so, abusive litigation would have nothing to do with the right to access courts. Instead, it would simply be about the use of court process and associated legal costs as a means to an impermissible end, likely to cause appreciable damage to fundamental rights.

Abusive litigation falls under the doctrine of abuse of process as its own nuanced and particular subset, distinguishable from ulterior motive or vexatious litigation. It requires a consideration of both the merits and the motivation. The merits are relevant to the question of whether the plaintiff has a right to vindicate. The motive for bringing the case is relevant to the true object of the litigation. The likely effects of the suit bring into the reckoning what harm to free expression may result.

As such, the Court did indeed strike the correct balance between the respective rights. Had the Court found that the merits of the case is the only determining factor, with no consideration to the motivation behind bringing the action, then the right to freedom of expression would have been unduly limited. Similarly, if motive were the only determining factor, then meritorious claims would be at risk of being dismissed, infringing the right to access to courts.

Further, the two considerations of motive and merit influence each other in that a case which lacks merit has plainly been brought for a reason other than to vindicate a right. However, the Court left it open to parliament to consider whether a more comprehensive, specific SLAPP suit defence of the kind developed in other jurisdictions, ought to be legislated in South Africa.

Because this appeal to the Constitutional Court originated from the dismissal of an exception taken against the SLAPP suit special plea in the High Court, it will now be for the High Court to determine whether the activists have successfully established a SLAPP suit defence in terms of the requirements established by the Constitutional Court.

Conclusion

Having found that a SLAPP suit defence can be accommodated under the common law doctrine of abuse of process, the Constitutional Court struck a delicate balance between freedom of expression and access to courts. However, the question that remains is how this defence will work in practice in light of the fact that this special plea requires a consideration of the merits at a preliminary stage of the trial before any evidence has been led.

The nuanced and technical nature of this defence begs the question as to whether it would have been better left to parliament to provide the much-needed guidance and structure on how the defence will work in practice. Perhaps a few more SLAPPs will clarify the matter.