South Africa, the Rainbow Nation that only loves certain colours of the Rainbow?

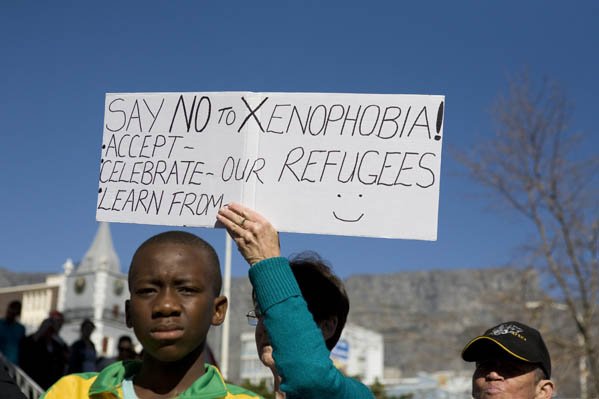

Fan Walk For Peace And Unity, Charlies's Bakery, a highly successful Cape Town based bakery, organised a fan walk to celebrate the 92nd birthday of Nelson Mandale, a state hero that was also dedicated to create awareness of xenophobia in the South Africa, 18 July 2010, Janah Hattingh, Creative Commons.

Editors’ note: This post constitutes a part of a blog series on the Protection of Refugees’ and Migrants’ Rights in Africa. According to a report by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Africa is home to over 30 million internally displaced persons, refugees, and asylum seekers. This translates to the African continent being home to nearly one-third of the world’s refugee population. Over the past three years, these figures have increased, triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic, climate change, new conflicts, and ongoing human rights violations. Against this background, this series features contributions from legal experts and practitioners reflecting on the legal framework providing for the promotion and protection of the rights of migrants and refugees, and the unique problems that minorities confront in this system due to factors such as race and gender discrimination.

The post-apartheid era has seen the golden age of transformative laws and policies, providing rights and legal entitlements for the previously disadvantaged within South Africa. However, in as much as South Africa has celebrated over 28 years of democracy, that democracy can rightly be argued to exclude non-South Africans. Do we intend to equally provide basic rights to all persons within our borders or is South Africa a rainbow nation that only loves certain colours of the rainbow?

South Africa has a distinct approach to asylum claims in which they are not adjudicated in terms of our immigration laws or through direct reliance on International Refugee Law. Instead, our asylum system is delineated through the promulgation of its own legislation, which establishes an urbanized asylum system, meaning that any asylum seeker or refugee should be able integrate into the community because they are afforded freedom of movement and access to all basic human rights, including healthcare, education and employment.

The Refugees Act 130 of 1998 (“Refugees Act”) had been in operation for over 20 years without any substantial amendments until recently. During this period, however, we saw a consistent pattern of court intervention to ameliorate gaps within the legislation and prevent its unlawful infringement. The courts have adjudicated on matters such as asylum seekers’ right to study and seek employment, the standard required in adjudicating asylum claims, ensuring that State departments include dependants born after an asylum application was made, and re-opening certain Refugee Reception Offices unlawfully closed.

Implementation of the Refugees Act has been so marred by State corruption and inefficiency that projects have to be launched in collaboration with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees to reduce the backlog of outstanding asylum decisions, where some applicants have waited over a decade for a decision. One could argue that South Africa has never properly implemented the Refugees Act, creating a fractured and dysfunctional system.

South Africa has an obligation in terms of international law and section 2 of the Refugees Act to fulfil the principle of non-refoulement. This principle, enshrined in Article 33 of the 1951 Refugee Convention and crystallized into a rule of Customary International Law, prohibits States from returning any person to a country where they may face harm or where their life is at risk. Non-compliance within our borders is described as an act of indirect-refoulement, in which the State, unwilling to integrate asylum seekers and refugees, makes conditions so untenable that they are forced to return to the country they fled from.

Regardless of legal interventions, we have seen a rise in xenophobia not just from a social perspective, but a political one too. The State has consistently pushed to create circumstances of indirect refoulement and to use the general public to do so, crafting a narrative through public statements that have a clear bias towards asylum seekers, refugees and foreign nationals. These statements blame foreign nationals for high unemployment rates, crime and, most recently, for poor delivery of basic healthcare at hospitals. The State has even gone so far as to accuse NGO’s of playing the victim card.

These public sentiments galvanize a non-existent crisis, spurring different community reactions and directly creating xenophobic tensions within South Africa. We have also seen a number of politicians using this xenophobic rhetoric to further their own political agendas concerning elections and votes. However, the most obvious form of indirect refoulement is through the promulgation of new laws and policies, as well as the narrow interpretation of existing ones, by State Departments who facilitate such undertakings. Court orders can enact a legal change but without a change in South Africans’ perception and understanding, can we truly say we are meeting our obligation to provide asylum to those in need?

“Court orders can enact a legal change but without a change in South Africans’ perception and understanding, can we truly say we are meeting our obligation to provide asylum to those in need?”

On 1 January 2020, we saw the promulgation of substantial amendments to the Refugees Act, with little to no regard for submissions from relevant stakeholders within the sector highlighting the proposed changes’ deficiencies. The sentiment of the amendments reflects the intention of indirect-refoulement. The asylum seeking process has changed from a State official (with relevant training) being obligated to prove an applicant’s claim in a non-adversarial manner into an approach placing an applicant in an adversarial position having to prove their claim, without, in most cases, any assistance or legal knowledge about the standard required for establishing a well-founded fear of persecution. This once again evidenced the State’s unwillingness to comply with its international obligations.

The full extent these amendments’ impact on the asylum sector has not been fully appreciated due to the COVID-19 pandemic and closure of the State Departments just two months after their enactment. The pandemic has brought its own challenges, wherein asylum seekers and refugees became forgotten. Even though the State introduced a system for the renewal of visas and permits for asylum seekers and refugees during the pandemic, two years later there has been no move towards resuming normal services and it is one of the few departments where all services have not recommenced despite lifting of the State of Disaster. Asylum seekers and refugees remain undocumented due to barriers in understanding the online renewal system and backlogs once again being created and exacerbated by the State.

Although South Africa’s urbanised asylum system obligates the State to provide socio-economic protection to asylum seekers and refugees, it prioritises the health and safety of South African citizens. During the pandemic, grants were mostly provided only to refugees and only through legal intervention were the Social Relief of Distress grants made available to asylum seekers. The same administrative difficulties experienced with the asylum system were experienced by asylum seekers in accessing grants because of their lack of documentation and State malaise in ensuring the system was operating efficiently. Even with the vaccine, lobbying once again had to take place from the civil society sector before foreign nationals could obtain vaccinations because the system created required a South African identification number.

In an effort to prevent the notion that the State propagates xenophobia, a National Action Plan to Combat Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance was introduced. But do such plans reek of disguised change? This plan was put into operation in 2019 before amendment of the Refugees Act, which evidences a clear disconnect between the action plan and the introduction of new policies and legislation. More recently, we have seen an example of this in the State’s proposed introduction of the National Labour Migration Policy and Employment Services Amendment Bill, where the definitions limit, rather than provide access and opportunities for refugees and asylum seekers to seek employment.

The consistent pattern of non-compliance with our obligations to refugees and asylum seekers raises questions about what steps need to be taken to appropriately sustain the Refugees Act and whether South Africa can or will take such steps.